Few days in the past we had a chat by Gergely Neu, who offered his latest work:

I am penning this put up largely to bother him, by presenting this work utilizing tremendous hand-wavy intuitions and cartoon figures. If this is not sufficient, I’ll even discover a strategy to point out GANs on this context.

However in truth, I am simply excited as a result of for as soon as, there’s a little little bit of studying principle that I half-understand, at the very least at an intuitive degree, because of its reliance on KL divergences and the mutual info.

A easy guessing recreation

Let’s begin this with a easy thought experiment for instance why and the way mutual info could also be helpful in describing an algorithm’s capability to generalize. Say we’re given two datasets, $mathcal{D}_{prepare}$ and $mathcal{D}_{check}$, of the identical measurement for simplicity. We play the next recreation: we each have entry to $mathcal{D}_{prepare}$ and $mathcal{D}_{check}$, and we each know what studying algorithm, $operatorname{Alg}$ we’ll use.

Now I toss a coin and I preserve the end result (recorded as random variable $Y$) a secret. If it is heads, I run $operatorname{Alg}$ on the coaching set $mathcal{D}_{prepare}$. If it is tails, I run $operatorname{Alg}$ on the check knowledge $mathcal{D}_{check}$ as an alternative. I do not let you know which of those I did, I solely disclose to you the ultimate parameter worth $W$. Are you able to guess, simply by taking a look at $W$, whether or not I skilled on coaching or check knowledge?

In case you can’t guess $Y$, that implies that the algorithm returns the identical random $W$ no matter whether or not you prepare it on coaching or check knowledge. So the coaching and check losses grow to be interchangeable. This means that the algorithm will generalize very nicely (on common) and never overfit to the info it is skilled on.

The mutual info, on this case between $W$ and $Y$ quantifies your theoretical capability to guess $Y$ from $W$. The upper this worth is, the simpler it’s to inform which dataset the algorithm was skilled on. If it is simple to reverse engineer my coin toss from parameters, it implies that the algorithm’s output may be very delicate to the enter dataset it is skilled on. And that probably implies poor generalization.

Observe by: an algorithm generalizing nicely on common does not imply it really works nicely on common. It simply implies that there will not be a big hole between the anticipated coaching and anticipated check error. Take for instance an algorithm returns a randomly initialized neural community, with out even touching the info. That algorithm generalizes extraordinarily nicely on common: it does simply as poorly on check knowledge because it does on coaching knowledge.

Illustrating this in additional element

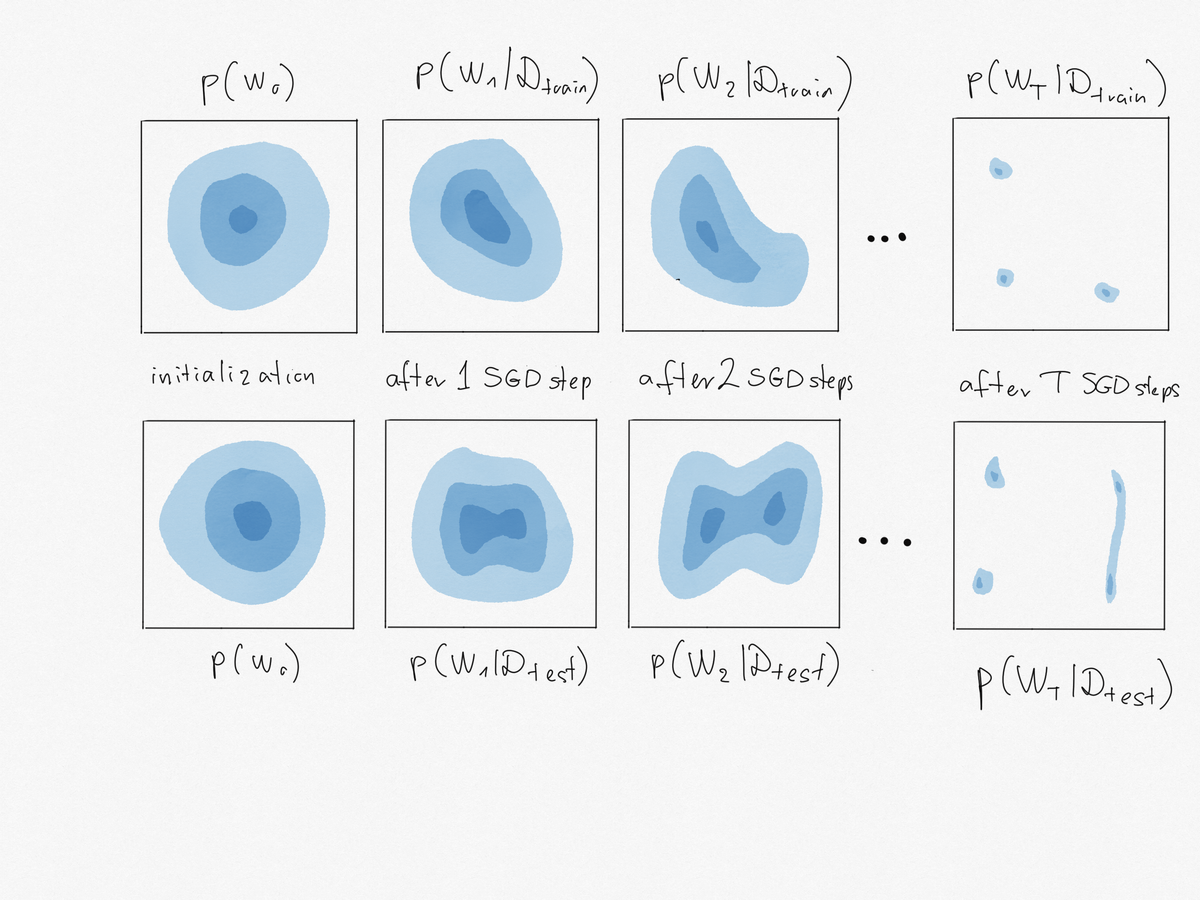

Under is an illustration of my thought experiment for SGD.

Within the prime row, I doodled the distribution of the parameter $W_t$ at numerous timesteps $t=0,1,2,ldots,T$ of SGD. We begin the algorithm by initializing $W$ randomly from a Gaussian (left panel). Then, every stochastic gradient replace modifications the distribution of $W_t$ a bit in comparison with the distribution of $W_{t-1}$. How the form of the distribution modifications is dependent upon the info we use within the SGD steps. Within the prime row, as an instance I ran SGD on $mathcal{D}_{prepare}$ and within the backside, I run it on $mathcal{D}_{check}$. The distibutions $p(W_tvert mathcal{D})$ I drew right here describe the place the SGD iterate is more likely to be after $t$ steps of SGD began from random initialization. They don’t seem to be to be confused with Bayesian posteriors, for instance.

We all know that operating the algorithm on the check set would produce low check error. Due to this fact, sampling a weight vector $W$ from $p(W_Tvert mathcal{D}_{check})$ could be nice if we may try this. However in follow, we won’t prepare on the check knowledge, all we have now the flexibility to pattern from is $p(W_Tvert mathcal{D}_{prepare})$. So what we might like for good generalization, is that if $p(W_Tvert mathcal{D}_{check})$ and $p(W_Tvert mathcal{D}_{prepare})$ had been as shut as doable. The mutual info between $W_T$ and my coinflip $Y$ measures this closeness by way of the Jensen-Shannon divergence:

$$

mathbb{I}[Y, W_T] = operatorname{JSD}[p(W_Tvert mathcal{D}_{test})|p(W_Tvert mathcal{D}_{train})]

$$

So, in abstract, if we will assure that the ultimate parameter an algorithm comes up with would not reveal an excessive amount of details about what dataset it was skilled on, we will hope that the algorithm has good generalization properties.

Mutual Inforrmation-based Generalization Bounds

These obscure intuitions will be formalized into actual information-theoretic generalization bounds. These had been first offered in a basic context in (Russo and Zou, 2016) and in a extra clearly machine studying context in (Xu and Raginsky, 2017). I will give a fast – and presumably considerably handwavy – overview of the primary outcomes.

Let $mathcal{D}$ and $mathcal{D}’$ be random datasets of measurement $n$, drawn i.i.d. from some underlying knowledge distribution $P$. Let $W$ be a parameter vector, which we get hold of by operating a studying algorithm $operatorname{Alg}$ on the coaching knowledge $mathcal{D}$: $W = operatorname{Alg}(mathcal{D})$. The algorithm could also be non-deterministic, i.e. it might output a random $W$ given a dataset. Let $mathcal{L}(W, mathcal{D})$ denote the lack of mannequin $W$ on dataset $mathcal{D}$. The anticipated generalization error of $operatorname{Alg}$ is outlined as follows:

$$

textual content{gen}( operatorname{Alg}, P) = mathbb{E}_{mathcal{D}sim P^n,mathcal{D}’sim P^n, Wvert mathcal{D}sim operatorname{Alg}(mathcal{D})}[mathcal{L}(W, mathcal{D}’) – mathcal{L}(W, mathcal{D})]

$$

If we unpack this, we have now two datasets $mathcal{D}$ and $mathcal{D}’$, the previous taking the position of the coaching dataset, the latter of the check knowledge. We have a look at the anticipated distinction between the coaching and check losses ($mathcal{L}(W, mathcal{D})$ and $mathcal{L}(W, mathcal{D}’)$), the place $W$ is obtained by operating $operatorname{Alg}$ on the coaching knowledge $mathcal{D}$. The expectation is taken over all doable random coaching units, check units, and over all doable random outcomes of the educational algorithm.

The data theoretic sure states that for any studying algorithm, and any loss operate that is bounded by $1$, the next inequality holds:

$$

gen(operatorname{Alg}, P) leq sqrt{frac{mathbb{I}[W, mathcal{D}]}{n}}

$$

The primary time period within the RHS of this sure is the mutual infomation between the coaching knowledge mathcal{D} and the pararmeter vector $W$ the algorithm finds. It primarily quantifies the variety of bits of data the algorithm leaks concerning the coaching knowledge into the parameters it learns. The decrease this quantity, the higher the algorithm generalizes.

Why we won’t apply this to SGD?

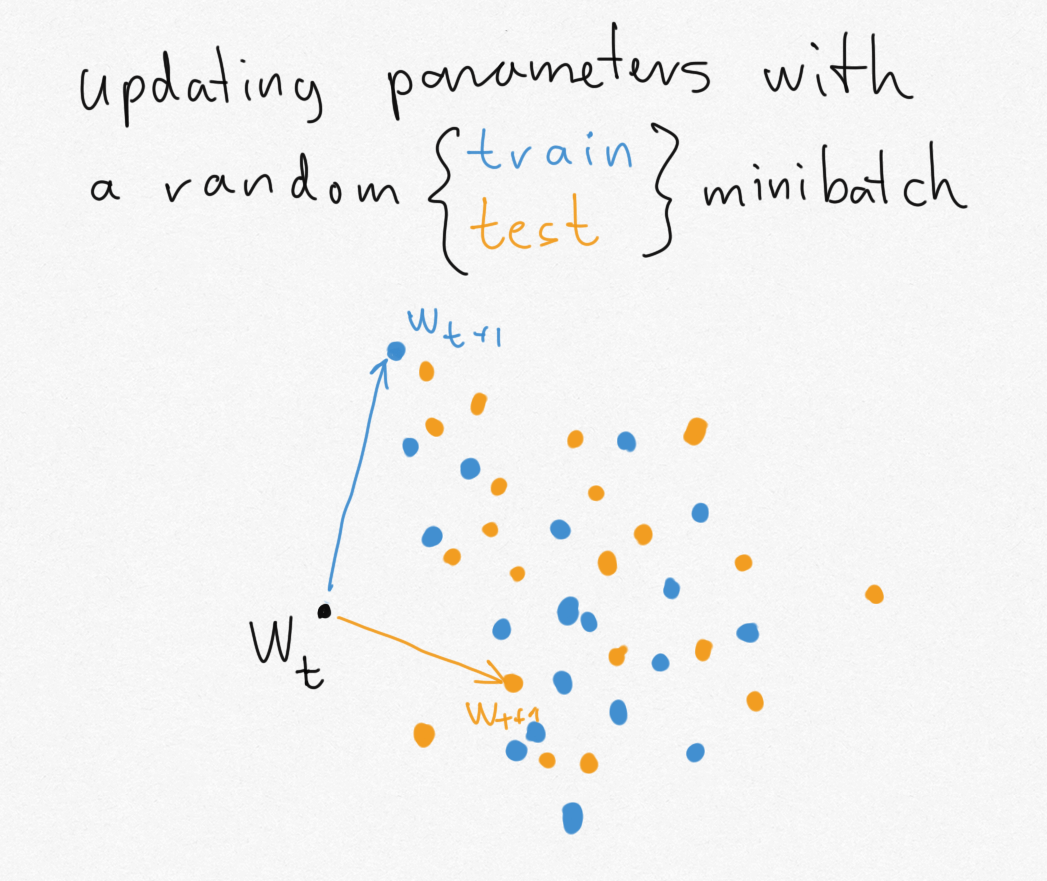

The issue with making use of these good, intuitive bounds to SGD is that SGD, in actual fact, leaks an excessive amount of details about the particular minibatches it’s skilled on. Let’s return to my illustrative instance of getting to guess if we ran the algorithm on coaching or check knowledge. Contemplate the situation the place we begin kind some parameter worth $w_t$ and we replace both with a random minibatch of coaching knowledge (blue) or a random minibatch of check knowledge (orange).

Because the coaching and check datasets are assumed to be of finite measurement, there are solely a finite variety of doable minibatches. Every of those minibatches can take the parameter to a singular new location. The issue is, the set of places you may attain with one dataset (blue dots) doesn’t overlap with the set of places you may attain when you replace with the opposite dataset (orange dots). Out of the blue, if I offer you $w_{t+1}$, you may instantly inform if it is an orange or blue dot, so you may instantly reconstruct my coinflip $Y$.

Within the extra basic case, the issue with SGD within the context of information-theoretic bounds is that the quantity of data SGD leaks concerning the dataset it was skilled on is excessive, and in some circumstances might even be infinite. That is truly associated to the issue that a number of of us seen within the context of GANs, the place the true and pretend distributions might have non-overlapping assist, making the KL divergence infinite, and saturating out the Jensen-Shannon divergence. The primary trick we got here up with to resolve this downside was to easy issues out by including Gaussian noise. Certainly, including noise is vital what researches have been doing to use these information-theoretic bounds to SGD.

Including noise to SGD

The very first thing folks did (Pensia et al, 2018) is to check a loud cousin of SGD: stochastic gradient Langevin dynamics (SGLD). SGDL is like SGD however in every iteration we add a little bit of Gaussian noise to the parameters along with the gradient replace. To grasp why SGLD leaks much less info, contemplate the earlier instance with the orange and blue level clouds. SGLD makes these level clouds overlap by convolving them with Gaussian noise.

Nevertheless, SGLD is just not precisely SGD, and it is not likely used as a lot in follow. To be able to say one thing about SGD particularly, Neu (2021) did one thing else, whereas nonetheless counting on the thought of including noise. As a substitute of baking the noise in as a part of the algorithm, Neu solely provides noise as a part of the evaluation. The algorithm being analysed continues to be SGD, however once we measure the mutual info we’ll measure the mutual info between $mathbb{I}[W + xi; mathcal{D}]$, the place $xi$ is Gaussian noise.

I go away it to you to take a look at the small print of the paper. Whereas the findings fall wanting explaining whether or not SGD have any tendency to search out options that generalise nicely, a number of the outcomes are good and interpretable: they join the generalization of SGD to the noisiness of gradients in addition to the smoothness of the loss alongside the particular optimization path that was taken.