March 30, 2023

A number of years in the past I used to be very a lot into most likelihood-based generative modeling and autoregressive fashions (see this, this or this). Extra just lately, my focus shifted to characterising inductive biases of gradient-based optimization focussing totally on supervised studying. I solely very just lately began combining the 2 concepts, revisiting autoregressive fashions throuh the lens of inductive biases, motivated by a want to know a bit extra about LLMs. As I did so, I discovered myself stunned by numerous observations, which actually shouldn’t have been shocking to me in any respect. This submit paperwork a few of these.

AR fashions > distributions over sequences

I’ve all the time related AR fashions as only a sensible option to parametrize chance distributions over multidimensional vectors or sequences. Given a sequence, one can write

$$

p(x_1, x_2, ldots, x_N;theta) = prod_{n=1}^{N} p(x_nvert x_{1:n-1}, theta)

$$

This fashion of defining a parametric joint distribution is computationally helpful as a result of it’s considerably simpler to make sure correct normalization of a conditional chance over a single variable than it’s to make sure correct normalization over a combinatorially extra complicated area of whole sequences.

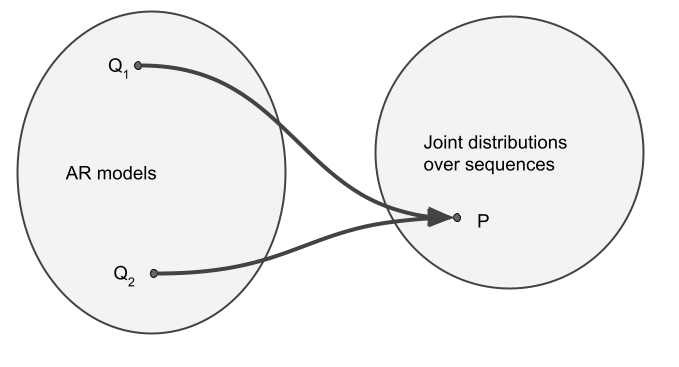

In my head, I thought-about there to be a 1-to-1 mapping between autoregressive fashions (a household of conditional chances ${p(x_nvert x_{1:n-1}), n=1ldots N}$) and joint distributions over sequences $p(x_1,ldots,x_N)$. Nonetheless, I now perceive that’s, typically, a many-to-one mapping.

Why is that this the case? Take into account a distribution over two binary variables $X_1$ and $X_2$. For example that, $mathbb{P}(X_1=0, X_2=0) = mathbb{P}(X_1=0, X_2=1) = 0$, that means that $mathbb{P}(X_1=0)=0$, i.e. $X_1$ all the time takes the worth of $1$. Now, think about two autoregressive fashions, $Q_1$ and $Q_2$. If these fashions are to be according to $P$, they need to agree on some details:

- $mathbb{Q}_1[X_2=xvert X_1=1] = mathbb{Q}_2[X_2=xvert X_1=1] = mathbb{P}[X_2=xvert X_1=1] = mathbb{P}[X_2=x]$ and

- $mathbb{Q}_1[X_1=1] = mathbb{Q}_2[X_1=1] = 1$.

Nonetheless, they will fully disagree on the conditional distribution of $X_2$ on condition that the worth of $X_1$ is $0$, for instance $mathbb{Q}_1[X_2=0vert X_1=0] =1$ however $mathbb{Q}_2[X_2=0vert X_1=0] =0$. The factor is, $X_1$ isn’t truly $0$ underneath both of the fashions, or $P$, but each fashions nonetheless specify this conditional chance. So, $Q_1$ and $Q_2$ usually are not the identical, but they outline precisely the identical joint distribution over $X_1$ and $X_2$.

Zero chance prompts

The that means of the above instance is that two AR fashions that outline precisely the identical distribution over sequences can arbitrarily disagree on how they full $0$-probability prompts. Let’s take a look at a extra language modely instance of this, and why this issues for ideas like systemic generalisation.

Let’s think about becoming AR fashions on a dataset generated by a probabilistic context free grammar $mathbb{P}[S=”a^nb^n”]=q^n(1-q)$. To make clear my notation, it is a distribution over sentences $S$ that take are fashioned by numerous `a` characters adopted by the identical variety of `b` charactes. Such a langauge would pattern $ab$, $aabb$, $aaabbb$, and so on, with reducing chance, and solely these.

Now think about two autoregressive fashions, $Q_1$ and $Q_2$, which each completely match our coaching distribution. By this I imply that $operatorname{KL}[Q_1|P] = operatorname{KL}[Q_2|P] = 0$. Now, you possibly can ask these fashions completely different sorts of questions.

- You may ask for a random sentence $S$, and also you get random samples returned, that are indistinguishable from sampling from $P$. $Q_1$ and $Q_2$ are equal on this state of affairs.

- You need to use a bizarre sampling methodology, like temperature scaling or top-p sampling to provide samples from a special distribution than $P$. It is a very fascinating query what this does, however if you happen to do that in $Q_1$ and $Q_2$, you’d nonetheless get the identical distribution of samples out, so the 2 fashions can be equal, assuming they each match $P$ completely.

- You may ask every mannequin to finish a typical immediate, like $aaab$. Each fashions will full this immediate precisely in the identical means, responding $bb$ and the top of sequence token. The 2 fashions are equal by way of completions of in-distribution prompts.

- You may ask every mannequin to finish a immediate that will by no means naturally be seen, like $aabab$, the 2 fashions are not equal. P would not prescribe how this damaged immediate ought to be accomplished because it would not comply with the grammar. However each $Q_1$ and $Q_2$ will provide you with a completion, they usually could give fully completely different ones.

When requested to finish an out-of-distribution immediate, how will the fashions behave? There is no such thing as a proper or incorrect means to do that, no less than not that one can derive from $P$ alone. So, as an instance:

- $Q_1$ samples completions like $mathbf{aabab}b$, $mathbf{aabab}bab$, $mathbf{aabab}bbaba$, whereas

- $Q_2$ samples $mathbf{aabab}$, $mathbf{aabab}bbb$, $mathbf{aabab}bbbbbb$.

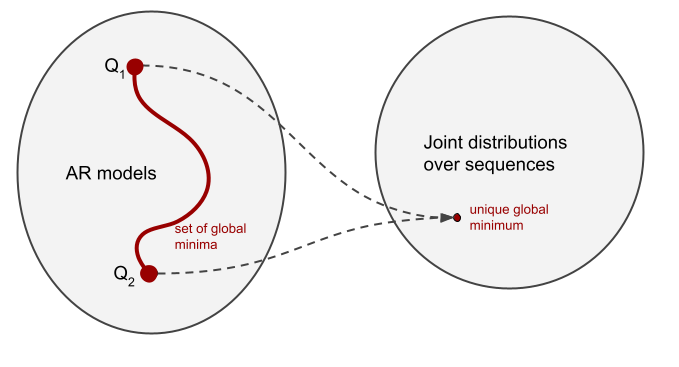

On this instance we are able to describe the behaviour of every of the 2 fashions. $Q_1$ applies the rule “the variety of $a$s and $b$s have to be the identical”. This can be a rule that holds in $P$, so this mannequin has extrapolated this rule to sequences outdoors of the grammar. $Q_2$ follows the rule “after getting seen a $b$ you shouldn’t generate any extra $a$s”. Each of those guidelines apply in $P$, and in reality, the context free grammar $a^nb^n$ might be outlined because the product of those two guidelines (due to Gail Weiss for pointing this out throughout her Cambridge go to). So we are able to say that $Q_1$ and $Q_2$ extrapolate very in another way, but, they’re equal generative fashions no less than as far as the distribution of sequences is worried. They each are world minima of the coaching loss. Which one we’re extra possible t get because of optimization is as much as inductive biases. And naturally, there’s extra than simply these two fashions, there are infinitely many various AR fashions according to P that differ of their behaviour.

Consequence for max probability coaching

An essential consequence of that is that mannequin probability alone would not inform us the complete story in regards to the high quality of an AR mannequin. Regardless that cross entropy is convex within the area of chance distributions, it isn’t strictly convex within the area of AR fashions (except the info distribution locations non-zero chance mass on all sequences, which is completely not the case with pure or laptop language). Cross entropy has a number of – infinitely many – world minima, even within the restrict of infinite coaching information. And these completely different world minima can exhibit a broad vary of behaviours when requested to finish out-of-distribution prompts. Thus, it’s all the way down to inductive biases of the coaching course of to “select” which minima are likelier to be reached than others.

Low chance prompts

However absolutely, we’re not simply involved in evaluating language fashions on zero chance prompts. And the way can we even know if the prompts we’re utilizing are really zero chance underneath the “true distribution of language”? Nicely, we do not really want to think about really zero chance promots. The above remark can possible be softened to think about AR fashions’ behaviour on a set of prompts with small enough chance of prevalence. Here’s a conjecture, and I go away it to readers to formalize this absolutely, or show some easy bounds for this:

Given a set $mathcal{P}$ of prompts such that $mathbb{P}(mathcal{P}) = epsilon$, it’s potential to seek out two fashions $Q_1$ and $Q_2$ such that $Q_1$ and $Q_2$ approximate $P$ effectively, but $Q_1$ and $Q_2$ give very completely different completions to prompts in mathcal{P}.

Consequence: as long as a desired ‘functionality’ of a mannequin might be measured by evaluating completions of an AR mannequin on a set of prompts that occurr with small chance, cross-entropy can not distinguish between succesful and poor fashions. For any language mannequin with good efficiency on a restricted benchmark, we can discover one other language mannequin that matches the unique on cross entropy loss, however which fails on the benchmark fully.

A very good illustration of the small chance immediate set is given by Xie et al (2021) who interpret in-context studying capacity of language fashions as implicit Bayesian inference. In that paper, the set of prompts that correspond to in-context few-shot studying prompts have vanishing chance underneath the mannequin, but the mannequin provides significant responses in that case.

Language Fashions and the Interpolation Regime

Through the years, a lot of mathematical fashions, ideas and evaluation regimes have been put ahead in an try and generate significant explanations of the success of deep studying. One such concept is to review optimization within the interpolation regime: when our fashions are highly effective sufficient to realize zero coaching error, and mimimizing the coaching loss thus turns into an underdetermined downside. The fascinating excellent query turns into which of the worldwide minima of the coaching loss our optimization selects.

The eventualities typically studied on this regime embrace regression with a finite variety of samples or separable classification the place even a easy linear mannequin can attain zero coaching error. I am very excited in regards to the prospect of learning AR generative fashions within the interpolation regime: the place cross entropy approaches the entropy of the coaching information. Can we are saying one thing in regards to the varieties of OOD behaviour gradient-based optimization favours in such circumstances?