I needed to spotlight an intriguing paper I introduced at a journal membership lately:

There’s truly a associated paper that got here out concurrently, finding out full-batch gradient descent as an alternative of SGD:

Some of the necessary insights in machine studying over the previous few years pertains to the significance of optimization algorithms in generalization efficiency.

Why deep studying works in any respect

With a purpose to perceive why deep studying works in addition to it does, it’s inadequate to motive concerning the loss perform or the mannequin class, which is what classical generalisation idea focussed on. As an alternative, the algorithms we use to seek out minima (particularly, stochastic gradient descent) appear to play an necessary function. In lots of duties, highly effective neural networks are in a position to interpolate coaching information, i.e. obtain near-0 coaching loss. There are in reality a number of minima of the coaching loss that are nearly indistinguishably good on the coaching information. A few of these minima generalise nicely (i.e. end in low check error), others may be arbitrarily badly overfit.

What appears to be necessary then shouldn’t be whether or not the optimization algorithm converges shortly to a neighborhood minimal, however which of the out there “nearly international” minima it prefers to succeed in. It appears to be the case that the optimization algorithms we use to coach deep neural networks desire some minima over others, and that this desire ends in higher generalisation efficiency. The desire of optimization algorithms to converge to sure minima whereas avoiding others is described as implicit regularization.

I wrote this word as an summary on how we/I presently take into consideration why deep networks generalize.

Analysing the impact of finite stepsize

One of many fascinating new theories that helped me think about what occurs in deep studying coaching is that of neural tangent kernels. On this framework we research neural community coaching within the restrict of infinitely large layers, full-batch coaching and infinitesimally small studying fee, i.e. when gradient turns into steady gradient move, described by an abnormal differential equation. Though the speculation is beneficial and interesting, full-batch coaching with infinitesimally small studying charges could be very a lot a cartoon model of what we truly do in follow. In follow, the smallest studying date would not all the time work greatest. Secondly, the stochasticity of gradient updates in minibatch-SGD appears to be of significance as nicely.

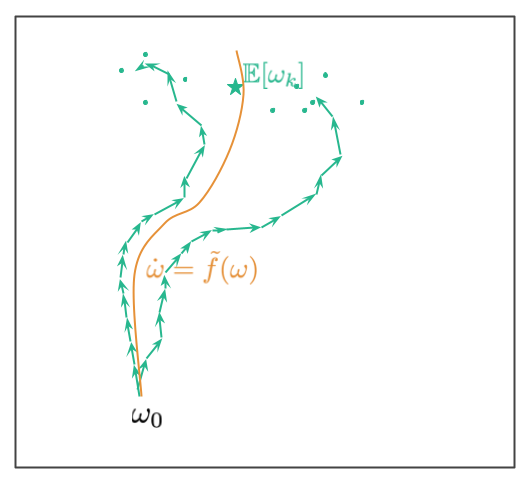

What Smith et al (2021) do in another way on this paper is that they attempt to research minibatch-SGD, for small, however not infinitesimally small, studying charges. That is a lot nearer to follow. The toolkit that enables them to check this situation is borrowed from the research of differential equations and is named backward error evaluation. The cartoon illustration beneath exhibits what backward error evaluation tries to attain:

For instance we have now a differential equation $dot{omega} = f(omega)$. The answer to this ODE with preliminary situation $omega_0$ is a steady trajectory $omega_t$, proven within the picture in black. We normally cannot compute this answer in closed type, and as an alternative simulate the ODE utilizing the Euler’s technique, $omega_{ok+1} = omega_k + epsilon f(omega_k)$. This ends in a discrete trajectory proven in teal. On account of discretization error, for finite stepsize $epsilon$, this discrete path could not lie precisely the place the continual black path lies. Errors accumulate over time, as proven on this illustration. The purpose of backward error evaluation is to discover a completely different ODE, $dot{omega} = tilde{f}(omega)$ such that the approximate discrete path we acquired from Euler’s technique lieas close to the the continual path which solves this new ODE. Our purpose is to reverse engineer a modified $tilde{f}$ such that the discrete iteration may be well-modelled by an ODE.

Why is this convenient? As a result of the shape $tilde{f}$ takes can reveal fascinating points of the behaviour of the discrete algorithm, significantly if it has any implicit bias in direction of transferring into completely different areas of the area. When the authors apply this method to (full-batch) gradient descent, it already suggests the form of implicit regularization bias gradient descent has.

In Gradient descent with a price perform $C$, the unique ODE is $f(omega) = -nabla C (omega)$. The modified ODE which corresponds to a finite stepsize $epsilon$ takes the shape $dot{omega} = -nablatilde{C}_{GD}(omega)$ the place

$$

tilde{C}_{GD}(omega) = C(omega) + frac{epsilon}{4} |nabla C(omega)|^2

$$

So, gradient descent with finite stepsize $epsilon$ is like working gradient move, however with an added penalty that penalises the gradients of the loss perform. The second time period is what Barret and Dherin (2021) name implicit gradient regularization.

Stochastic Gradients

Analysing SGD on this framework is a little more tough as a result of the trajectory in stochastic gradient descent is, nicely, stochastic. Due to this fact, you do not have have a single discrete trajectory to optimize, however as an alternative you may have a distribution of various trajectories which you’d traverse when you randomly reshuffle your information. This is an image illustrating this example:

Ranging from the preliminary level $omega_0$ we now have a number of trajectories. These correspond to alternative ways we are able to shuffle information (within the paper we assume we have now a hard and fast allocation of datapoints to minibatches, and the randomness comes from the order by which the minibatches are thought of). The 2 teal trajectories illustrate two potential paths. The paths find yourself at a random location, the teal dots present extra random endpoints the place trajectories could find yourself at. The teal star exhibits the imply of the distribution of random trajectory endpoints.

The purpose in (Smith et al, 2021) is to reverse-engineer an ODE in order that the continual (orange) path lies near this imply location. The corresponding ODE is of the shape $dot{omega} = -nabla C_{SGD}(omega)$, the place

$$

tilde{C}_{SGD}(omega) = C(omega) + frac{epsilon}{4m} sum_{ok=1}^{m} |nabla hat{C}_k(omega)|^2,

$$

the place $hat{C}_k$ is the loss perform on the $ok^{th}$ minibatch. There are $m$ minibatches in whole. Notice that that is much like what we had for gradient descent, however as an alternative of the norm of the full-batch gradient we now have the typical norm of minibatch gradients because the implicit regularizer. One other fascinating view on that is to take a look at the distinction between the GD and SGD regularizers:

$$

tilde{C}_{SGD} = tilde{C}_{GD} + frac{epsilon}{4m} sum_{ok=1}^{m} |nabla hat{C}_k(omega) – C(omega)|^2

$$

This extra regularization time period, $frac{1}{m}sum_{ok=1}^{m} |nabla hat{C}_k(omega) – C(omega)|^2$, is one thing like the full variance of minibatch gradients (the hint of the empirical Fisher info matrix). Intuitively, this regularizer time period will keep away from components of the parameter-space the place the variance of gradients calculated over completely different minibatches is excessive.

Importantly, whereas $C_{GD}$ has the identical minima as $C$, that is not true for $C_{SGD}$. Some minima of $C$ the place the variance of gradients is excessive, is not a minimal of $C_{SGD}$. As an implication, not solely does SGD observe completely different trajectories than full-batch GD, it might additionally converge to utterly completely different options.

As a sidenote, there are a lot of variations of SGD, based mostly on how information is sampled for the gradient updates. Right here, it’s assumed that the datapoints are assigned to minibatches, however then the minibatches are randomly sampled. That is completely different from randomly sampling datapoints with substitute from the coaching information (Li et al (2015) contemplate that case), and certainly an evaluation of that variant could nicely result in completely different outcomes.

Connection to generalization

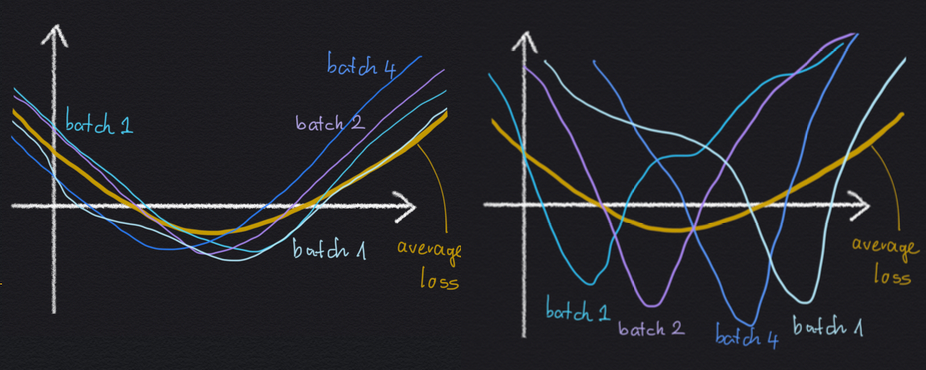

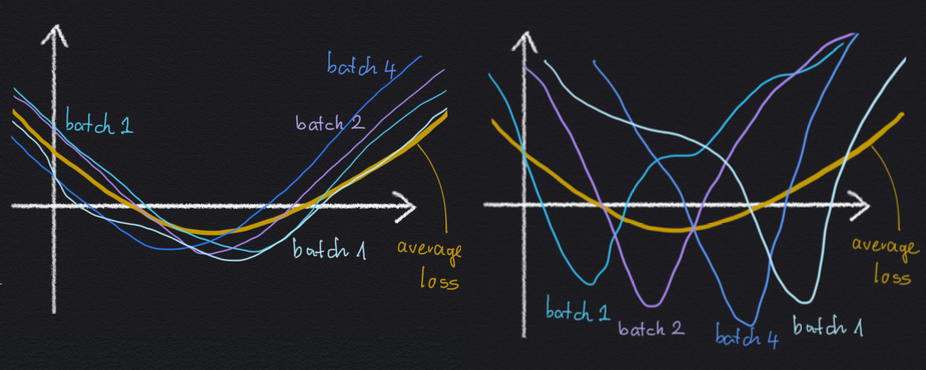

Why would an implicit regularization impact avoiding excessive minibatch gradient variance be helpful for generalisation? Nicely, let’s contemplate a cartoon illustration of two native minima beneath:

Each minima are the identical as a lot as the typical loss $C$ is anxious: the worth of the minimal is identical, and the width of the 2 minima are the identical. But, within the left-hand state of affairs, the large minimal arises as the typical of a number of minibatch losses, which all look the identical, and which all are comparatively large themselves. Within the right-hand minimal, the large common loss minimal arises as the typical of plenty of sharp minibatch losses, which all disagree on the place precisely the situation of the minimal is.

If we have now these two choices, it’s affordable to anticipate the left-hand minimal to generalise higher, as a result of the loss perform appears to be much less delicate to whichever particular minibatch we’re evaluating it on. As a consequence, the loss perform additionally could also be much less delicate as to if a datapoint is within the coaching set or within the check set.

Abstract

In abstract, this paper is a really fascinating evaluation of stochastic gradient descent. Whereas it has its limitations (which the authors do not attempt to cover and focus on transparently within the paper), it nonetheless contributes a really fascinating new method for analysing optimization algorithms with finite stepsize. I discovered the paper to be well-written, with the reason of considerably tedious particulars of the evaluation clearly laid out. However maybe I favored this paper most as a result of it confirmed my intuitions about why SGD works, and what sort of minima it tends to desire.